Bringing Competition to Walled Gardens

Third-Party Browsers & Web Apps - VERSION 1.2

You can also download the PDF version [7.7MB]

1. Table of Contents

2. Preface

To the Safari/Webkit Team,

To anyone who works on Safari/Webkit who reads this document, the authors would like to note that all criticism of Safari/Webkit is aimed squarely at Apple and Apple's upper management. We would like to acknowledge your many groundbreaking contributions to the Web over the past two decades.

As people that have dedicated their lives to building browsers we know you care deeply about the open web and may privately disagree with Apple's anti-competitive practices. We also understand that Safari/Webkit’s funding and which features are approved is entirely controlled from above. We understand that building a browser is an enormous, complex undertaking and that it’s not possible to keep up with a modern feature set while making the platform stable without significant investment, despite the hard-work and dedication of each individual.

We also understand that Apple operates under a paranoid air of strict secrecy which can make it difficult for you to engage properly with the development community and that employees can be fired for even mild criticism of the company making it hard for effective change from within. We hope that this document can help start that change.

Our main aim is to ensure open competition so that the Web and Web Apps can compete against the closed proprietary ecosystems. The future of the web is apps, if native can do it, so can the web except with privacy and security built in by design. It is our strong hope that Webkit will meaningfully participate in this future.

Many of us have developed with Safari and Webkit since it first came out and were inspired to build mobile web apps by Steve Job’s 2007 speech with the platform that your team built. The web we use today is built on your legacy. It is our hope that with this competition Apple will come to realize the great importance of Safari and Webkit to their overall business goals and will provide the resources and funding to make it the best, most private, stable and feature rich browser available.

Thank-you for your hard work and for everything you’ve given us, we hope you will continue to fight for a better open-web.

3. Introduction

The entire future of the consumer application industry is being heavily limited by Apple’s ban of third-party browsers. These actions prevent cross-compatibility between devices, and create significant barriers for new market entrants. For businesses and consumers, it greatly increases costs and enables Apple to lock them into their closed ecosystem. This reduces competition for both browsers and applications, and shifts the cycle of investment and funding from an open and free platform to proprietary closed platforms, driving up prices for consumers and developers.

Apple has banned competing Third-Party Browsers from their iOS devices (iPhone and iPad) by requiring that all browser vendors use Safari’s WebView (2.5.6 App Store Review Guidelines). Browser vendors are not allowed to ship their browsers which they have spent hundreds of thousands of hours developing and instead are forced to produce a separate browser which is essentially a thin wrapper or skin around the WebKit engine in Apple’s own browser, Safari.

Critically this browser ban prevents the emergence of an open and free universal platform for apps, where developers can build their application once and have it work across all consumer devices, be it desktop, laptop, tablet or phone. Instead it forces companies to create multiple separate applications to run on each platform, significantly raising the cost and complexity of development and maintenance. These costs are in addition to the 15% - 30% tax charged by the App Store. This greater cost is ultimately passed on to consumers in the form of higher fees, more bug prone applications and the applications not being available on all platforms. This then decreases competition with other manufacturers by depriving them of a healthy library of apps. The costs of developing an interoperable application that works identically are pushed so high that only well funded companies can afford it and as a result many useful or otherwise profitable applications never get built.

Apple is preventing the interoperable, standards-based web from becoming a viable alternative to the native proprietary ecosystems on offer from Apple and Google. In the absence of competition, the poor state of Apple’s own browser and integration of Web Apps has the effect of pushing developers and users towards the gated ecosystem of the App Store. Safari and Apple’s WebView frequently suffer simultaneous, critical application breaking bugs which spill into competing iOS browsers because they cannot bring their own engines which might not contain these bugs.

In a clear conflict of interest with third-party browsers, Apple receives 15b USD per year for search engine placement in Safari while ensuring other browsers can not effectively compete on iOS, its most popular operating system. Mozilla, a non-profit, produces a browser that consistently bests Apple’s in security and standards conformance with revenues of less than $500 million per year.

A lack of market pressure, combined with alleged systemic underfunding over many years, prevents the web from becoming a viable application platform. The only way for developers to create stable, capable applications is to invest in Apple’s proprietary platform, which it taxes and retains exclusive control over.

Individual companies benefit greatly from locking users in and their competitors out. Apple hides behind claims of extra security and privacy when, in fact, their restrictions deprive the consumer of choice and locks their data and purchases into Apple’s walled garden. This prevents or adds great friction to users moving to competing platforms by hampering interoperability.

Web Apps add an extra layer of security and privacy controls to native application platforms, improving on the operating system’s built-in controls leading to enhanced user safety. If allowed, Web Apps can offer equivalent functionality with greater privacy and security for demanding use-cases that are traditionally the domain of less secure native apps. A free & universal development and distribution platform is what leads to competition and an investment cycle in free and open software that benefits businesses and consumers.

Two key remedies from regulation can serve to restore meaningful competition:

- Reversing Apple’s ban on competing browsers and browser engines

- Compelling full integration and functionality for apps built with open web technology, including on competing browsers

The future of consumer application development depends on these changes.

3.1 This Document

This document outlines the primary issues related to Browsers and Web Apps and the future of consumer application development.

3.2 Open Web Advocacy

Open Web Advocacy is a loose group of software engineers from all over the world, who work for many different companies who have come together to fight for the future of the open web by providing regulators, legislators and policy makers the intricate technical details that they need to understand the major anti-competitive issues in our industry and potential ways to solve them.

It should be noted that all the authors and reviewers of this document are software engineers and not economists, lawyers or regulatory experts. The aim is to explain the current situation, outline the specific problems, how this affects consumers and suggest potential regulatory remedies.

This is a grassroots effort by software engineers as individuals and not on behalf of their employers or any of the browser vendors. We came together with the hope of creating a better world since no major company has been pushing for this change in recent years. The majority of the engineers behind this document have decided to remain anonymous as no individual feels comfortable going up against the world’s most valuable company, particularly one that is so litigious.

We are available to regulators, legislators and policy makers for presentations / Q&A and we can provide expert technical analysis on topics in this area.

For those who would like to help or join us in fighting for a free and open future for the web, please contact us at:

- contactus@open-web-advocacy.org

- @OpenWebAdvocacy

- Web

- https://open-web-advocacy.org

3.3 Definitions

"Third-Party Browser" - A web browser developed by a company other than the gatekeeper which includes a layout engine and rendering engine either selected or built by the company.

"Native App" - An app written using a gatekeeper’s proprietary frameworks and APIs which are provided by the operating system. On iOS (Apple’s operating system for iPhone and iPad) these are currently exclusively delivered through Apple’s App Store.

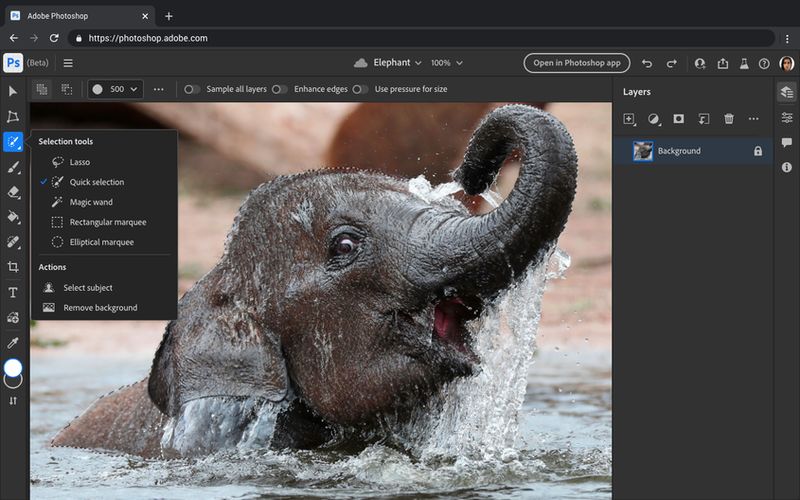

"Web App" - A Web Application, Web App or Progressive Web App (PWA) is an application developed using Web technologies, such as HTML, CSS, JavaScript and WebAssembly. Web Apps use Web Browsers as the "engine" to run the Web App. The capabilities of a Web Apps depends on the level of advancement of the Web Browser that they run on. WebAssembly allows developers to bring existing software, for example game engines or photoshop, and port/convert them so they run on the web or as a web-app.

Web Apps can be made to run offline, can run as smoothly as native apps and can support high performance applications, but this functionality depends on the Web Browser. Web Apps offer more privacy and security than native apps. Web Apps are universal, in that they can be written once and then run on all devices. This is in comparison with native apps that have to be rewritten for each platform that they target.

To the end user a well written Web App should be indistinguishable from a native app.

"WebView Browser" - A web browser that does not include its own engine, and instead uses an engine or an unmodified "WebView" provided by the OS. For example all browsers on iOS other than Safari on iOS are WebView browsers, in that they do not render the website or run the code for the site and instead hand that job onto Safari WebView.

"PWA (Progressive Web App)" - Can be used interchangeably with Web App, although PWA is used to describe modern Web Apps with functionality that is typically associated with native apps rather than websites (i.e. installation on device, Offline Storage, Device API access etc). For the purposes of this document Web App and PWA will be treated identically.

"Gatekeeper" - The company that controls the operating system and the apps that run on that operating system (i.e. Apple with iOS, Google with Android).

"Browser Vendor" - The entity that makes the browser.

4. Effective Competition?

Businesses that face effective competition dare not raise prices, or cut down on quality standards, for fear of losing customers to their competitors (and so losing money) Dr Michael Grenfell

For the foreseeable future, iOS will be the dominant access pathway, passport, monetizer and platform for not just digital life, but virtual ones. Apple holds this role because it makes best-in-class hardware, offers the best apps, and operates the most lucrative app store. Matthew Ball - Venture Capitalist, Writer

iOS Safari faces no effective competition as Apple has banned the engines that differentiate other browsers. Customers have little recourse short of buying another phone.

The development, maintenance and lost opportunity costs of supporting a buggy browser that misses key features are mostly hidden from them. It is hard for consumers to see a missing feature or an entire Web App that didn’t get built (due to poor support in iOS Safari). When they do encounter a bug caused by Safari they are more likely to blame the Web App than the browser. The user may get the impression that the web is buggy, slow and that native apps are better, which then has negative flow on effects for the entire web ecosystem.

Businesses have little recourse as they can not suggest their customers install another real browser (there are none) and they are unwilling to lose more than half their mobile customers (51% in the UK, 66% in Japan, 56% in Australia, 46% in the US). Additionally iOS users tend to be wealthier and spend more making them a higher priority for companies. In the end the majority of large businesses simply throw in the towel and make an iOS Native App and in doing so agree to pay Apple 15-30% of their revenue.

As such, Apple faces little effective competitive pressure to improve the quality of their iOS Safari browser and has incentives to inhibit it from competing with native. Thus Apple’s decade long prohibition on competition for Safari on iOS has a compounding anti-competitive effect as companies sink money into non-interoperable native iOS applications instead of Web Apps.

Even Apple executives appear to be aware only their stranglehold on iOS installation is allowing their 30% tax on revenue, something they can not achieve on macOS.

Neither is on the store because they don't have to be. They can be on Mac and distribute to users without sharing the revenue with us Philip Schiller - Apple Upper Management - On the Mac App Store

5. Apple is Holding Back the Open Web

Instead, Apple is inhibiting this future Internet. And it does so via tolls, controls, and technologies that not only deny what made and still makes the open web so powerful, but also prevents competition, and prioritize Apple’s own profits. Matthew Ball - Venture Capitalist, Writer

Making the web less useful makes apps more useful, from which Apple can take its share; similarly, it is notable that Apple is expanding its own app install product even as it is kneecapping the industry’s. Ben Thompson - Stratechery

5.1. Steve Jobs' Original Vision for iOS

Steve Jobs’ original vision for third-party apps on iOS was quite different from today’s status quo.

The following is a transcript of a speech he gave announcing Web Apps as the platform for third-party iOS developers, including his thoughts on security, deployment, and criticisms of other distribution models (emphasis added):

Now, what about developers?

We have been trying to come up with a solution to expand the capabilities of iPhone by allowing developers to write great apps for it, and yet keep the iPhone reliable and secure. And we’ve come up with a very sweet solution.

Let me tell you about it.

So, we’ve got an innovative new way to create applications for mobile devices, really innovative, and it’s all based on the fact that iPhone has the full Safari inside. The full Safari engine is inside of iPhone and it gives us tremendous capability, more than there’s ever been in a mobile device to this date, and so you can write amazing Web 2.0 and Ajax apps that look exactly and behave exactly like apps on the iPhone!

And these apps can integrate perfectly with iPhone services: they can make a call, they can send an email, they can look up a location on Google Maps. After you write them, you have instant distribution.

You don’t have to worry about distribution: just put them on your internet server. And they’re really easy to update: just change the code on your own server, rather than having to go through this really complex update process.

They’re secured with the same kind of security you’d use for transactions with Amazon, or a bank, and they run securely on the iPhone so they don’t compromise its reliability or security.

And guess what: there’s no SDK! You’ve got everything you need, if you know how to write apps using the most modern web standards, to write amazing apps for the iPhone today.

You can go live on June 29.

Steve Jobs - Original Announcement of Third-Party Apps (2007)

Apple invented mobile Web Apps, but ultimately decided on a proprietary closed ecosystem.

5.2 Apple Claims that Web Apps are a Viable Alternative to the App Store

Web Apps are applications installed from the browser that utilize the user's browser to give users an experience on par with Native apps. They are interoperable between operating systems, have a [very tight security/privacy model](very tight security/privacy model) and are capable of amazing things.

Apple’s original vision for applications on iOS was Web Apps, and today they still claim Web Apps are a viable alternative to the App Store. Apple CEO Tim Cook made a similar claim last year in Congressional testimony when he suggested the web offers a viable alternative distribution channel to the iOS App Store. They have also claimed this during a court case in Australia with Epic.

Despite this Web Apps are not currently a viable competitor to the iOS App Store for three reasons:

- Browser Ban

Apple’s Safari is the only browser on iOS as all other browsers have been effectively banned - Missing Features

Apple has refused to implement key features (some for more than 10 years) that would allow Web Apps to compete with the App Store, both in iOS and in Safari. - Bugs

Apple's iOS Safari is significantly more buggy and unstable than its rivals making it unviable as a platform for applications.

5.3 Apple has effectively banned all Third-Party browsers

The Apple App Store Review Guidelines contain the following rule:

2.5.6 Apps that browse the web must use the appropriate WebKit framework and WebKit Javascript.

Webkit is the engine that powers Safari and several Linux browsers. Apple also produces a "WebKit framework" that is included in its operating systems (macOS, iOS, iPadOS, tvOS, and watchOS).

In practice, Section 2.5.6 is a requirement that iOS and iPadOS browsers from Google, Microsoft, Mozilla, Samsung, Opera cannot use their own engines the way they do everywhere else. These engines take hundreds of thousands of engineer hours to develop, and are excluded from Apple’s most successful consumer operating systems. Competing browser vendors are only allowed to produce shells around a very specific, unaltered version of Safari’s WebView; a component whose features Apple dictates.

All rival iOS browsers in the App Store are essentially Safari under the hood. This Browser Ban is unique to Apple’s iOS.

Apple has a browser monopoly on iOS, which is something Microsoft was never able to achieve with IE Scott Gilbertson - The Register

All of this is compounded by yet another Apple policy: no third-party browser engines. You can install apps like Chrome, Firefox, Brave, DuckDuckGo, and others on the iPhone — but fundamentally they’re all just skins on top of Apple’s WebKit engine. That means that Apple’s decisions on what web features to support on Safari are final. If Apple were to find a way to be comfortable letting competing web browsers run their own browser engines, a lot of this tension would dissipate. Dieter Bohn and Tom Warren - The Verge

So it’s not just one browser that falls behind. It’s all browsers on iOS. The whole web on iOS falls behind. And iOS has become so important that the entire web platform is being held back as a result. Niels Leenheer - HTML5test

because WebKit has literally zero competition on iOS, because Apple doesn’t allow competition, the incentive to make Safari better is much lighter than it could (should) be. Chris Coyier - CSS Tricks

What Gruber conveniently failed to mention is that Apple’s banning of third-party browser engines on iOS is repressing innovation in web apps. Richard MacManus - NewsStack

No other major operating system imposes a ban on integrated third-party browsers (browsers that include their own engines). Microsoft Windows, Android, Linux, and Apple’s own macOS all enable choice of integrated browser. Even Google’s ChromeOS, named after its browser, is more open to competing engines than iOS.

Despite this uniquely anti-competitive situation, Apple has managed to evade regulatory oversight. Browser choice is what drives the technology forward which ultimately results in better, faster, more reliable software for users.

Microsoft’s IE6 was once the dominant browser with a 95% market share 1 due to its pre-installation on Windows. Without competition on the Windows platform, browser development remained stagnant for years until Firefox’s market share triggered Microsoft to start investing in browsers once again. At no point did Microsoft ban competing browsers as Apple has done.

1 "Usage share of web browsers - Wikipedia." Accessed 23 Jun. 2021.

5.3.1 Hobbled Competition even within Safari clones

Apple's hobbling of third-party browsers doesn't stop at mandating a specific version of Webkit, Apple provides Safari significant unfair advantages.

The major issues include:

-

Full Screen Video

Safari is allowed to make video full screen, the other "browsers" are prevented from doing so, except on iPad.

It is hard to see the rationale for allowing it on iPad but disabling it on iPhone. -

Full Screen Games

Canvas, a software component, which is essential for Games can not be made full screen. Apple derives most of their App Store revenue from games. -

No Web Apps

The other "browsers" can not install Web Apps. Only Safari can. -

Extensions

Only Safari can use extensions which are used by many users, including to block advertising. -

Apple Pay

Apple limits the integration of Apple Pay with the other browsers. -

In-App Browsers

Regardless of the user’s default browser setting, iOS will always force the user to use Safari instead of the user’s choice of browser. An In-App Browser is a browser that you would see inside an application like twitter when you visit a link from inside the application.

5.4 Safari Lags Behind and is Missing Key Features

It’s well known in the web-development industry that Safari is far behind on critical web-features (emphasis added).

The reason we lost Safari on Windows is the same reason we are losing Safari on Mac. We didn't innovate or enhance Safari. If you want to compete on something across all platforms, it needs to be the best. We had an amazing start on Safari and then stopped innovating. Now, we are starting to work on Safari again but look at Chrome. They put out releases at least every month while we basically do it once a year Eddy Cue - Apple's Senior Vice President of Services

Apple's Safari lags considerably behind its peers in supporting web features Scott Gilbertson - The Register

Apple’s web engine consistently trails others in both compatibility and features, resulting in a large and persistent gap with Apple’s native platform. Alex Russell - Program Manager on Microsoft Edge

Safari just doesn’t support key features — and Safari’s the only option Dieter Bohn and Tom Warren - The Verge

It’s not just the lack of choice in browser engines on iOS, it’s that WebKit itself is deficient as a browser engine. Richard MacManus - The New Stack

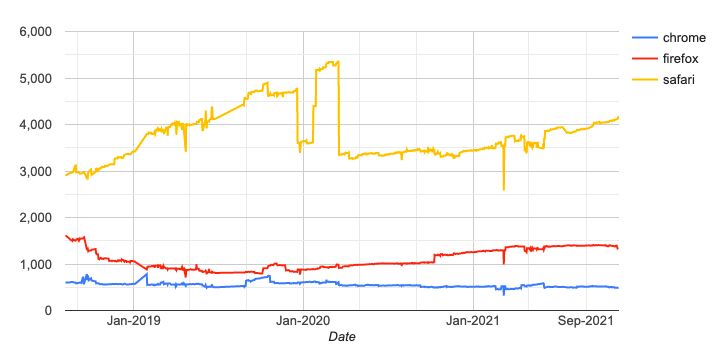

5.4.1 Web Platform Tests

The Web Platform Tests Dashboard shows this numerically by showing every failure that only fails in just one browser.

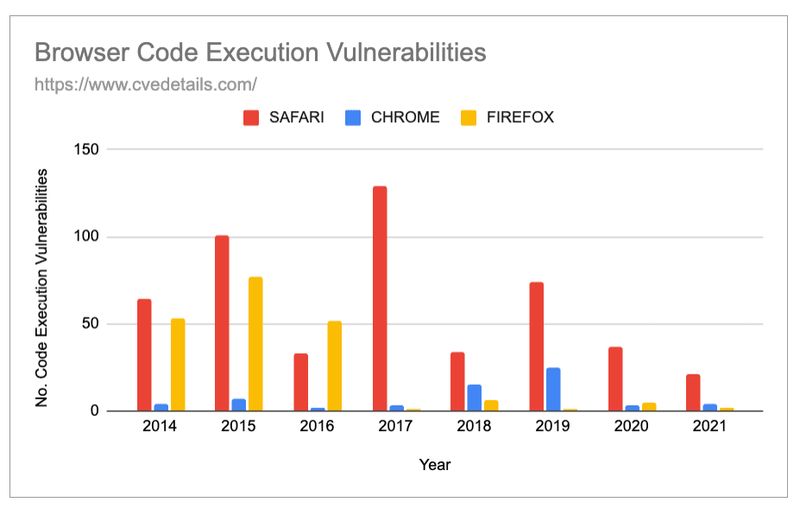

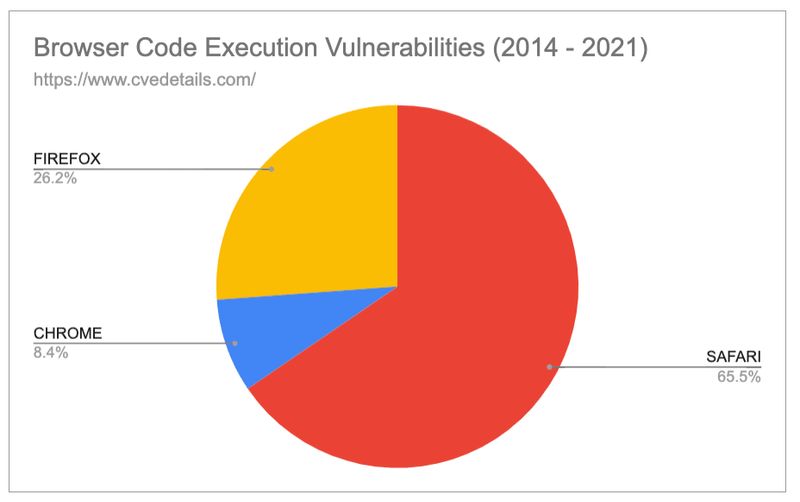

As can be seen as at 10/11/2021, for each of the experimental builds of these browsers:

- 4180 Failures - Safari

- 1346 Failures - Firefox

- 494 Failures - Chrome

Safari is objectively lagging the competition, and this is likely because Apple has no browser competition on the operating system most important to their business, iOS.

The Web Platform Tests Dashboard is a comprehensive test suite built by the developers of browsers themselves, including Mozilla, Google, Apple, Opera, and others. Not every browser supports every feature, and tests may vary in quality, but this is the closest to "ground truth" regarding the fine-grained detail of interoperability for all browsers. The failures listed above are only features that fail in just one browser.

5.4.2 Progressive Web App Feature Detector

The Progressive Web App Feature Detector is a high-level test that can provide directional understanding for developers attempting to assess the suitability of Web Apps for addressing their needs. It contains a short but important list of features that are used throughout native apps. Below is a comparison showing Chrome 95 running on a Samsung Galaxy S20 on the left, and Safari running on an iPhone X with iOS 15.1 on the right.

5.4.3 Missing Functionality

Safari – or more specifically the WebKit engine that powers it – is well behind the competition.

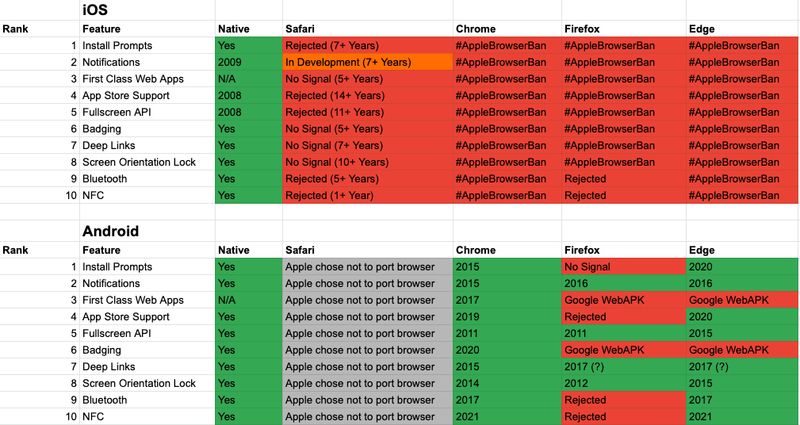

OWA identified the most important functionality specifically for Web Apps that are available on native or other browsers but missing in Safari.

This table exposes many anti-competitive issues, namely:

- Competing Browser’s on iOS are unable to implement functionality that they can on Android

- Apple has stagnated development and are many years behind the competition

- All of the functionality listed above is available for iOS Native Apps

- Google’s refusal to provide competitors a method of minting WebAPK’s prevents competing browsers from producing viable Web Apps.

5.4.3.1. Install Prompts (7+ Years Behind)

The ability to install Web Apps with at least the same level as ease as a native app. See 5.4.5. iOS Web App Installation - A well hidden Safari exclusive for more details.

This enables the developer to prompt to install a Web App when a user visits a website. For any implementation to be fair, it needs to match any requirements for native install prompts.

Success Criteria Include:

- The prompt needs to appear on the first load of the website OR by developer request. Since Apple acts as a gatekeeper they should not provide any preference to installing their own apps.

- The language used by the Install Prompts should not convey the idea that Web Apps are inferior to Native apps. I.e. they should use the same language as native apps. "Install" instead of "Add to Homescreen"

- The UI should be at a minimum equal in encouraging a user to install an app as the UIs provided on websites for installing native apps.

5.4.3.2. Notifications (7+ Years behind other browsers, 13+ years behind native)

Notifications are essential for a wide range of applications. Without notifications many apps can not function (i.e. Messaging Apps, Social Media apps etc). In general notification functionality should be equivalent to native.

Success criteria for notifications include:

-

The initial Enabling/Disable notifications prompt for an installed Web App should be equivalent to enabling notifications for a native app in terms of user experience and ease-of-use.

-

Delivery of notifications is equivalent to native applications including as it applies to reliability, speed (i.e. the time it takes the notification to reach the device) and whether or not the notification wakes the device when it is in "sleep mode".

-

Users should be able to enable / disable notifications in system settings in the same manner and ease that they enable / disable native apps.

5.4.3.3. First Class Web Apps (5+ Years behind)

"First Class Web Apps" is a general term that is used to describe a Web App that has equivalent integration into the operating system as a native app.

This includes:

- Settings

- Quick Launch Menus

- Integration with Voice Assistants

- Storage

Without full integration, this becomes a significant barrier to adoption. Businesses (especially large ones) will not take the risk of building Web Apps if they have any significant issues). The overarching principle to ensure Web Apps are able to compete is equality with native apps. That is, installing and managing a Web App should not be worse than installing and managing a native app.

There should be no suggestion to the user that a Web App is inferior or different from a native app.

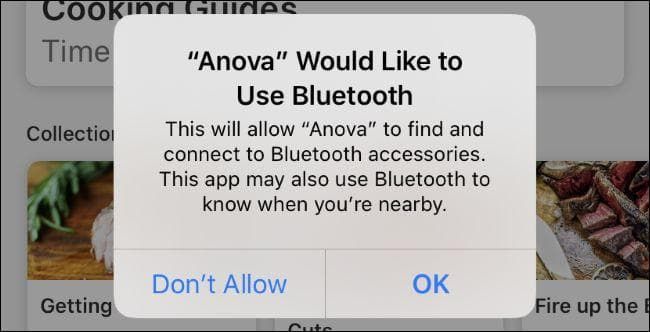

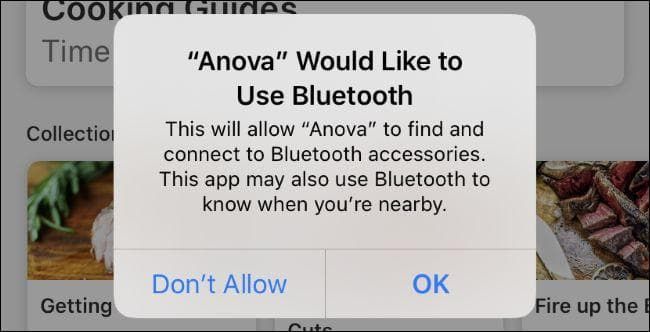

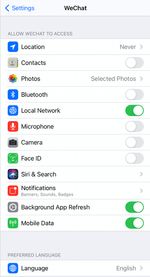

Double Prompts and the Permission Problem

Currently on iOS Web Apps are not considered as "real" apps by the operating system. They don’t show up on the settings menu, they don’t show up on App shortcuts, and they don’t appear on any of the privacy menus.

With the current architecture, for a Web-App to have permission to perform an action, Safari must have that permission. This is unobvious to all but experts. Therefore our recommendation is that permissions should be attached to the Web App itself and not to the browser.

For Example:

| Safari | Web App | Actual |

|---|---|---|

| Permission OFF | Permission ON | Permission ON |

| Permission ON | Permission ON | Permission ON |

| Permission OFF | Permission OFF | Permission OFF |

i.e. If Safari has notifications OFF and AmazingWebApp has notification ON, AmazingWebApp can still send notifications.

As the functionality of Web Apps in Safari improves, it will become critically important to enable users to have explicit control over what those Apps can and can’t do in a way that a normal user can understand.

User’s need to be able to easily grant and revoke permissions from web apps. This is essential for the success of Web Apps. As an example if users can not easily and individually disable and enable notifications per app, then user’s might be more inclined to preemptively block them thus providing a significant advantage to native ecosystems.

We recommend that all Web Apps should appear on the settings page and privacy pages identically to Native Apps.

This should include:

- Settings (Appearing on the settings page and in search)

- Privacy (Location Services / Bluetooth / Camera / Microphone etc)

- General > iPhone Storage

- General > Background App Refresh

- Siri Suggestions (With no order preference to native apps)

- Singleton Installations (i.e. the ability to only install a Web App once) is likely to be a prerequisite.

5.4.3.4. App Store Support (3+ Years behind)

Many companies will still want to list their Web Apps in the Apple AppStore. Android already provides this functionality with Trusted Web Activities.

Apple should provide a method where developers who have signed up to the Apple Developer Program can use an API to submit Web Apps to the Apple AppStore.

This should not require users to purchase an Apple Mac or require xcode (i.e. developers should be free to use Windows or Linux). It’s our belief that this will help drive Web App adoption.

5.4.3.5. Fullscreen API (11+ years behind)

Specific types of apps such as games require fullscreen to work properly. Apple currently only allows fullscreen for video and not for "canvas" which is required for games and other graphics intensive apps.

5.4.3.6. Badging (5+ years behind)

Badging which is outlined in more detail in section 5.4.4. Short Example allows the app to show a number to indicate the user that something has happened.

Users need the ability to disable badging and this should be managed in the same way badging is managed for native apps.

Success criteria include:

- Badges update at the same speed as native apps (including in the background)

- Badges can be enabled/disabled in the same manner as native apps.

5.4.3.7. Deep Links (7+ years behind)

Deep links also known as URL Protocol Handlers provide the ability to link into a Web App from another Web App or Native App via links.

Note that the equivalent has been available for a very long time in native apps.

5.4.3.8. Screen Orientation Lock (10+ Years Behind)

Screen Orientation Lock allows a user to lock the screen to either horizontal or vertical. This is essential to many types of apps, but especially games.

5.4.3.9. Bluetooth (5+ Years Behind)

Bluetooth allows apps to connect to printers / scanners / internet of things / toys. There are entire categories of apps that can’t be built without Web Bluetooth.

Discussed at length in 5.5.1. Fingerprinting and Web Device APIs

5.4.3.10. NFC (1+ Year Behind)

Apple has mentioned in regulatory filings issues with NFC and what is called Card Emulation Mode, but they have also refused to implement the entire Web NFC specification in Safari even though it doesn’t include Card Emulation Mode. Since they have effectively banned all other third-party browsers no other browser can provide NFC functionality.

So far Apple has not provided any detailed reasoning as to why they are blocking this functionality besides the following:

I'm not sure what specifics you're looking for but the issue is that we don't believe permission prompt is sufficient mitigation. Ordinary people don't understand the full security & privacy implications of granting NFC access when asked. Ryosuke Niwa - Apple

The Web NFC specification contains an extensive security and privacy section, but Apple has made little effort to productively convey or solve any perceived security issues. By only providing NFC functionality via its native ecosystem Apple effectively forces any developer that wishes to produce a mobile app with NFC to create a Native App where they can take a 30% cut.

As part of our submission we would argue that Apple should not be able to block NFC access to third-party browsers except where Apple applies on a demonstrably consistent basis to Apple's own Apps and Apps from the iOS App Store (including by rules with analogous intent).

Additionally any blocks should be narrowly tailored to solve particular security issues and Apple should be compelled to publicly answer and publicly provide technical documentation to any reasonable questions related to these rules or the evidence for them.

NFC has a huge range of current and future applications:

- Cashless payments

- Asset Tracking

- Time / Attendance / Check-In

- Businesses

- Universities

- Schools

- Opening Doors

- Hotels

- Houses

- Guest Access

- Corporate

- Ticketing

- Major Events

- Cinemas, Sporting Events, Concerts

- Transport (Public and Private)

- Pharmaceuticals

- Pairing Devices via Bluetooths

- WIFI without passwords, Guest Wifi

- Smart Posters

- Smart Cards

- Business Cards

- Passports / IDs

- Smart Home Integration

- Anti-Counterfeiting of real products

- App Shortcuts

- Multi-Factor Authentication

The door to innovation needs to be left open without Apple acting as the gatekeeper except to provide very narrow scope, heavily justified security, privacy or digital safety protections.

Our current recommendation is that Apple be forced to provide hardware access to NFC to other third-party browsers for the purposes of implementing the NFC specification (which currently only covers NDEF which is already provided to iOS native apps) and should be forced to expand that access as the Web NFC specification expands to cover other parts of NFC. In the case where Apple believes a security risk is too great to users, Apple should prove the harm to users is greater than the loss of utility.

5.4.3.11. Other Important Functionality

- General

- Push Notifications

- SQL (WebSQL or equivalent replacement)

- AV1/AVIF and VP8/VP9/WebP (open Media Codecs)

- Compression Streams

- Keyboard Lock and Keyboard Layout APIs

- Declarative Shadow DOM

- Reporting API

- Permissions API

- Screen Wakelock

- Intersection Observer V2

- Shared Workers and Broadcast Channels

- Background Sync

- Background Fetch API

- Essential Media APIs

- Background Audio in Third-Party Browsers and Web Apps. See WebKit bug, fix took 3 years.

- Features and functionality in PushKit

- Features and functionality in CallKit

- Essential Web App APIs

- Web App Install Prompts

- PWA App Shortcuts

- getInstalledRelatedApps()

- Periodic Background Sync

- Web Share Target

- Content Indexing

- Badging

- Device APIs

- Web Bluetooth

- Web NFC

- Web USB

- Web MIDI

- Web Serial

- Web HID

- Shape Detection

- Generic Sensors API

- Gaming and 3D-related APIs

- Fullscreen API for

<canvas>and other non-<video>elements - WASM Threads

- Shared Array Buffers

- SIMD

- WebXR

- Offscreen Canvas

- Fullscreen API for

The article Progress Delayed is Progress Denied is a detailed look at how far Safari has fallen behind in features.

Not every developer needs every feature listed above but some are the critical missing piece required to build a Web App instead of a Native App. For competition between Web Apps and Native Apps it’s important to compare the functionality of Web Apps with Native Apps and not simply between browsers

5.4.4. Short Example

To expand on each of these to explain why these missing features are important to developers would be a lengthy undertaking so instead we will highlight just a few and explain why they are essential to allow Web Apps to compete with the App Store. Please note that most of these capabilities or something analogous are possible in Native Applications.

Imagine you were building a social networking App and decided to build it as a Web App instead of as a Native App.

The two key pieces of functionality you would need to compete with the App Store would be being able to notify a user when they have received a new message (Push Notifications) and being able to add unread message count badges to the App Icon (App Badging). Both of these features are missing on iOS for Web Apps despite coming out for Native Apps more than 10 years ago. Multiple browsers support these features across many operating systems, both desktop and mobile whereas iOS Safari does not.

Twitter has built a high-quality Web App for Twitter that you can install on iOS but they still recommend you use the iOS Twitter App, likely due to these critical missing features.

An App Badge showing a count of 29 on iOS in 2011:

Because of these missing features entire categories of apps can either not be built using the web or which ensure that the native app is significantly better.

5.4.5. iOS Web App Installation - A well hidden Safari exclusive

Apple heavily preferences Native Apps while placing strong limitations on Web Apps.

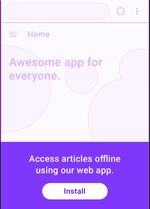

On Android devices, Web Apps are easy to find and install. Firefox / Chrome & Edge all provide functionality that allow developers to make installing Web Apps on Android simple, intuitive and easy.

By comparison it can be very difficult to explain to a user how to install a web-app on iOS through Safari, as it is hidden away and requires multiple steps to find. It could be argued that Apple benefits from this as it will drive companies to use native apps. Apple makes it easy to install native apps with Smart App Banners while making it very difficult to install Web Apps.

For the other reskinned/rebranded Safari WebView browsers (Chrome/Edge/Firefox) Apple has blocked them from installing Web Apps. This functionality is exclusive to Safari.

5.4.5.1. Android

On Android devices, the process for installing a Web App on either Firefox or Chrome is very straightforward and there are many options as shown by the following examples taken from web.dev.

Developers have a huge freedom of choice and can add installers in headers, footers, menu bars, and temporary pop-ups backed by an open API. This ensures that there is minimal difficulty installing a Web App on Android.

Finally there is a clearly marked "Install App" on the main menu. As demonstrated there is no barrier to installing Web Apps on Android systems and is made easy for developers to add and users to use.

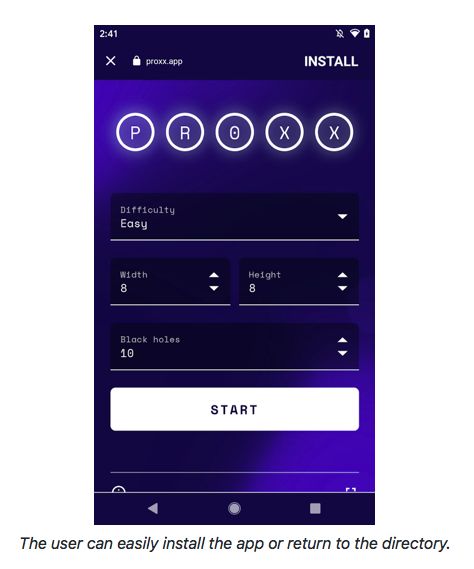

As a real life example, the game PROXX displays a pop-up bottom banner when you first play, sliding that up displays more information about the app. Tapping install can directly install the app although the exact experience differs between different manufacturers devices.

5.4.5.2. iOS Safari

The process on iOS Safari is considerably more difficult and quite a bit more hidden and awkward. The majority of users we have asked do not know the functionality exists and have never used it. Apple has refused to implement this feature without any good justification providing App Store apps a significant advantage over Web Apps.

On iOS, Apple makes installing native apps very easy with Smart App Banners while making installing open Web Apps as obscure as possible. Even when on phone support with users it can be difficult to explain how to add a Web App. This is not a problem on Android.

You can see in the example taken from Apple’s documentation that a link to the native app is prominently displayed at the top of the screen.

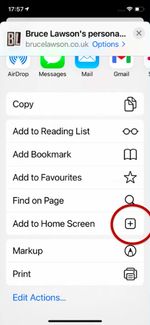

To install a Web App on iOS the current process is as follows:

Other "browsers" on iOS do not have the ability to install Web Apps.

This means that despite simply being thin user interface shells around Safari’s WebKit, every "browser" on iOS including Firefox, Chrome, Edge, Opera, Brave can not add Web Apps. Users visiting a Web App capable site in these browsers on iOS would not even find the install button unless they would know to switch to Safari, then go through the steps as described here. This is clearly evidence of Apple preferencing their browser and native apps.

5.4.5.3. App Clips

An App Clip is a micro-version of native iOS application which allows consumers to load and use part of the application without installing the full application.

App Clips as shown on Apple.com

This is good for native application developers who want to decrease friction by allowing users to nearly instantly preview or use a subsection of functionality. An App Clip does not require a user to have to go through the App Store, removing a key barrier.

As seen in the previous section, Apple has not implemented any way to inform users that they can install a Web App, and makes the whole installation process very cumbersome. In the meantime, Apple has added the ability for developers to display these native App Clip panels on top of web pages often to incite users to use a native app instead of the web page they are currently viewing.

Apple’s addition of this feature while at the same time ensuring that Web Apps are hidden away, difficult to install and have other barriers to adoption which increase user friction, is a clear demonstration of anti-competitive behaviour.

5.4.5.4. Smart App Banners

Apple has a technology called Smart App Banners. These are little banners that appear in Safari when visiting a url that matches the universal link patterns set for an App or by including a special meta tag.

If the App is not installed it displays a deep link to the iOS App Store. If the App is installed it provides a link to open the App on iOS.

According to this complaint there is no way for the developer to stop the Smart App Banner from appearing even if they do not add the meta-tag. Provided the universal link patterns set for an App match it will display the banner.

There is no meta-tag to disable this behavior, forcing all developers to include a banner on their Website even if they wish to disable it is a clear attempt to direct traffic off the Web and into Apple’s ecosystem. Smart App Banners should likely be opt-in and respect the developers wishes. At the very least developers should be able to opt-out.

5.4.5.5. Dark Patterns

Dark patterns are design elements that deliberately obscure, mislead, coerce and/or deceive website visitors into making unintended and possibly harmful choices. Misha Ketchell - The Conversation

The friction added to installing Web Apps by hiding away installation options, preventing the installation from other "browsers" and the clear preference shown to native apps through Smart Banners and App Clips are arguably dark patterns and can completely hobble developers' attempts to provide apps to their users through the open web.

Despite Apple’s claims to regulators that "PWA’s eliminate the need to download a developer’s app through the App Store (or other means)" the reality is that Apple has limited the user experience for Web Apps to the point where developers are forced to develop native apps.

5.5. Apple Uses Flawed Privacy Arguments

The most dangerous feature that browsers have are not the device API’s; it is the ability to link to and download native apps. Niels Leenheer - HTML5test

5.5.1. Fingerprinting and Web Device APIs

The goal of fingerprinting is to re-identify users uniquely (without their permission), this is typically for advertising purposes. This is done by collecting many different data points about the device (ip address, screen size, operating system version, existence of certain fonts). Each of those data points cannot identify an individual, but it could be possible to track users if you have enough of these data points and combine them.

Apple has rejected certain web standard device APIs that would provide Web Apps equivalent capabilities to Native Apps (the web standard versions are actually arguably much more strict and secure than their native counterparts, see Section 4.14 below).

Finally, if we find that features and web APIs increase fingerprintability and offer no safe way to protect our users, we will not implement them until we or others have found a good way to reduce that fingerprintability. Apple

This was the stated reason Apple used to reject WebBluetooth from Safari (Webkit). This doesn’t make a great deal of sense.

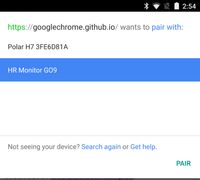

Bluetooth is a short-range, standardized wireless technology standard that is used for exchanging data between fixed and mobile devices over short distances. Web Bluetooth is an API that provides the ability to connect and interact with Bluetooth Low Energy peripherals (but not classic Bluetooth devices, for security reasons). For example printers, toys, scanners, lights, home automation, washing machines, dryers, scanners, payment devices and a huge list of other "Internet of Things" (IoT) devices.

With Web Bluetooth, a Web App can not get a list of bluetooth devices. Instead, only with user interaction (e.g., clicking on a button), can a site request the browser open a permission prompt to connect to a bluetooth device and the site can provide filters to potentially reduce the list to devices it can understand, but cannot skip the user’s consent. The list is made available to the user, not to the Website/Web App. The user can give access to a single device or deny access altogether.

This is a very unreliable method of fingerprinting and requires a scary permission prompt to the user on each Web App.

Similar arguments can be extended to each of the other hardware APIs, they are all difficult to use for fingerprinting as it's impossible to do so without alerting the users and requiring their permission.

Device API’s are simply bad for fingerprinting. It is unreliable and really obvious when it is used. Niels Leenheer - HTML5test

We are not saying that iOS Safari must implement every feature implemented by the other browsers, in fact it is healthy for browser makers to pursue their own vision for the web. What is a problem is that Apple has banned all other browsers, so on iOS users have no option to use a different browser that does support these APIs.

It should be expected that privacy and security standards that apply to the web should also apply to native apps where Apple derives their profit.

Apple by both not supporting these APIs in iOS Safari and banning all competing browsers, is making it impossible for Web Apps to compete with native apps in cases where these device APIs are a core or important part of the application.

It is important to note here that Apple in their rejection of Web Bluetooth and other Device APIs have focused on fingerprinting (as opposed to firmware hacks) despite doing a far poorer job in mitigating these risks in native. Possibly this is in a effort to frame the rejection of these features through the lens that both Apple is pro-privacy as opposed to a general belief that the web should not be an application platform on iOS, and as a slight on other browsers vendors/developers by implying they want these features in order to spy on users.

5.5.2. Native vs Web Privacy/Security

The web’s paranoid security model was not developed in a vacuum. Browsers have evolved to place a high value on security and privacy, and the same is true of the Web Bluetooth Security Model.

Behind each expansion of browser capabilities is a simple idea: if browsers do not provide important features, users will feel the need to install applications to meet their computing needs. It is also important to note that there is no discussion of entirely removing for example bluetooth from iOS (web and native).

Therefore, privacy and security risks must be viewed in terms of mitigation and in comparison with native apps. As such bluetooth is a useful example to compare web and native in utility/privacy and security. From this vantage point, we can compare the level of care taken by browsers in exposing bluetooth devices versus native apps.

5.5.2.1. Potential security/privacy concerns

A number of potential security and privacy issues have been raised by participants in the Working Group developing the Web Bluetooth standard:

These include:

- Malicious messages sent to poorly designed, or older, bluetooth devices.

A Website/Web App could connect to poorly designed older bluetooth devices and then hack them to launch further attacks on the user.

Note for this attack to work:- The device needs to be poorly designed without functionality that prevents an attacker from doing harmful actions. Note that most devices that offer a harmful actions have security protections in place (i.e. they required updates in place)

- The attacker needs to have specific code that targets that device, the user has to own that device and then ask to connect to that device and then the user has to give the website permission.

- The Web Bluetooth specification maintains a block-list of known-vulnerable devices which browsers are expected to block from connections.

- Browsers include the ability to strip permissions, including blocking the loading of, websites that act maliciously in this way (e.g. Google’s SafeBrowsing, used by Chrome and Firefox, and Microsoft SmartScreen)

- Collecting lists of nearby devices (for location tracking)

Shops could place bluetooth devices on their premises and a Website/Web App with completely unfettered access to bluetooth could connect to them thus revealing the users location without permission.

Thankfully, the Web Bluetooth specification prevents this ambient attack by creating the opportunity for a user to select the devices they wish to connect to before any data is sent. - Fingerprinting

The goal of fingerprinting is to reidentify users uniquely (without their permission), this is typically for advertising purposes. Typical fingerprinting is done by silently collecting many different data points on the website (ip address, screen size, operating system, existence of certain fonts). Each data point is unlikely to uniquely identify an individual, but it is possible to track users if you have enough of them. A user connecting to the same device on two different websites could uniquely identify the user.

Web Bluetooth adds a strong deterrent to ambient fingerprinting through the addition of a user-visible permission prompt. Permission-based APIs are not frequently used for fingerprinting today due to the low acceptance rates by users of these grants, making them nearly useless for pervasive, low-friction fingerprinting.

Risks endure for users who have elevated threats and clear their caches, but thanks to the permission model of Web Bluetooth, browsers can also inform users of the risks of re-identification at the time of use. By managing these capabilities more tightly than native OS APIs (which expose blanket grants to bluetooth stacks), browsers mitigate these risks more directly.

5.5.2.2. Process for connecting to a device on web and iOS native

5.5.2.2.1. Web

The process in the web specification is as follows:

- Upon a user gesture (click, touching a button etc) the Website/Web App may request to connect to a specific bluetooth device OR they may provide a specific category of device to be used as a filter.

- The browser displays a prompt to the user indicating that the Website / Web App would like to connect to a bluetooth enabled device and displays a list of devices.

The Website/Web App never gets to see this list of bluetooth devices, it may not connect to any device without specific consent. - If the user choices to connect to a device, the Website/Web App may now communicate with that specific device

- This permission can be revoked at any time via the browser but it is important to note it is only for this specific Website/Web App and only the specifically chosen device

5.5.2.2.2. iOS Native

The process for iOS native applications using Swift CoreBluetooth is:

- Declare that the application needs to use bluetooth along with a description in the info.plist *

- On first boot of the application, it will ask the user permission (via a prompt) to use bluetooth *

- If the user agrees the application now has access to bluetooth 2

- This permission can be revoked at any time via user settings

- The application can now get lists of any nearby bluetooth devices and connect/communicate with them indefinitely without user interaction.

2 Until 2019, steps 1 - 3 were not required. This means before 2019 that the very large number of apps with bluetooth permissions track all users and connect to any device.

5.5.2.3. How does iOS bluetooth for native apps mitigate these concerns?

The permission system on iOS is a bit more of a blank check. Once given initial Bluetooth permission, applications are essentially given free reign to do whatever they want with regards to Bluetooth. They can list all nearby devices (without user interaction) and they can communicate with any nearby Bluetooth device (without user interaction).

Prior to iOS 13 (late 2019) the situation was even worse. Applications did not even need to ask for bluetooth permission at all.

Many companies were using this to track users' locations without their consent. Shops were placing bluetooth beacons in their stores and then tracking users' physical location without consent. This was only possibly due to the weak security/privacy implementation on iOS Native CoreBluetooth. Note this still has not been fixed and this sort of abuse is still possible today, provided an application can convince a user that it has a plausible reason to provide access to bluetooth (a simple yes/no prompt).

All three of the above listed privacy/security concerns are currently essentially unmitigated except by:

- App Store Review (a dubious defense)

- The user giving permission to access bluetooth once

It's odd that Apple is not implementing Web-Bluetooth over security/privacy concerns and, in effect, forcing users to download a native app with far broader powers when they don't appear to have adopted equivalently strong protections within their native app ecosystem. Rejecting WebBluetooth on these grounds is nonsensical.

These issues still have not been fixed with native iOS Apps bluetooth permissions. Their APIs were not designed to enable a more respectful prompt the way the Web Bluetooth specification was, and shifting all existing applications to a less invasive model may break many unmaintained programs. In these tradeoffs Apple could choose user privacy and security and against invasive developers, but they have not, and yet they hold up the less problematic web API as an unacceptable risk.

When comparing risk in allowing a Web App feature, the comparison is not between the risk the feature brings and nothing (i.e not allowing the feature). The comparison is between the feature and getting the user to download a native application with an analogous feature.

As shown in the previous sections, with regards to bluetooth the web is far more restricted, secure and private than what is allowed in native. It could be argued that not allowing Web Bluetooth is actually worsening the user's risk profile, in addition to denying them convenient functionality. If the only alternative is to download a native app with far greater permissions then this arguably puts the user at greater risk.

Web Bluetooth is largely analogous to the other Device APIs.

Device APIs and File System Access are probably the most complex in terms of security privacy. There are legitimate security concerns (as there are with equivalent APIs for native applications). The web specifications have in our opinion largely mitigated these concerns (certainly far better than native apps on iOS have).

Apple has done an extremely poor job communicating what their concerns are (in sufficient technical detail, including why they think the mitigations are insufficient) to developers and other browser vendors.

5.5.2.4. Safari WebBluetooth Extension

Can't we solve this using browser extensions? Daniel Bates - Apple Webkit Team - 8th November 2017

In the last public discussion about Web Bluetooth Standard between Apple and the other browser vendors it was suggested that browser extensions could offer a potential solution.

The idea is that users who need Web Bluetooth could install a browser extension via the iOS App Store that provides this functionality to Safari. A prototype of this has been produced for iOS.

While developers producing these types of extensions are almost certainly just trying to help users, this solution is problematic for several reasons:

- Security/Privacy is hard, Device APIs are powerful and while they provide great utility this seems more a job for the dedicated teams at the browser vendors to handle.

- iOS Native has poor privacy protection relative to Web Bluetooth and the developer of these extensions would need to attempt to replicate all the mitigations in the extension itself.

- It is arguably a dark pattern to discourage usage of Web Apps vs Native Apps to add extra hoops for users wanting to use Bluetooth on the web. This style of solution would presumably be unacceptable for Native Apps.

5.5.2.5. Apple's Identifier for Advertisers (IDFA)

Apple has a tactical commitment to your privacy, not a moral one. When it comes down to guarding your privacy or losing access to Chinese markets and manufacturing, your privacy is jettisoned without a second thought. Cory Doctorow - Former European director of the Electronic Frontier Foundation

Given Apple’s strong stance on user privacy on the web, to the point of rejecting extremely useful functionality on the mere possibility that a user could be assigned a unique identifier it may surprise readers to learn that Apple offers a method to uniquely fingerprint users in native apps called Apple's Identifier for Advertisers (IDFA).

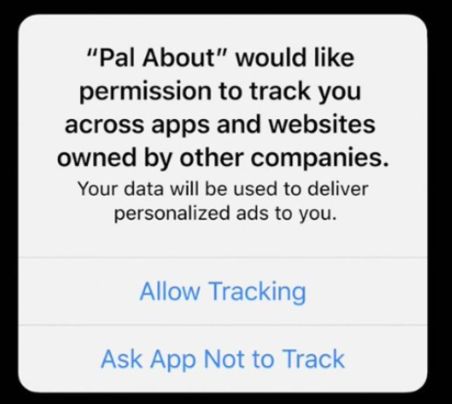

Up until iOS 10 there was no way for users to disable this, starting in iOS 14 users are asked via this slightly ambiguous prompt if they consent (about 20% of users have turned this operating system provided fingerprint off).

Even when users do turn this functionality off, due to Natives' very permissive privacy and security model (relative to the Web) Apps can continue to fingerprint users.

Our investigation found the iPhone’s tracking protections are nowhere nearly as comprehensive as Apple’s advertising might suggest. We found at least three popular iPhone games share a substantial amount of identifying information with ad companies, even after being asked not to track.

When we flagged our findings to Apple, it said it was reaching out to these companies to understand what information they are collecting and how they are sharing it. After several weeks, nothing appears to have changed. Geoffrey Fowler And Tatum Hunter - Washington Post

The only consistent privacy policy with Apple’s concern for uniquely fingerprinting users on the web and with users being tricked via prompt) would be to remove this functionality from iOS altogether.

Apple has not announced any plans to entirely remove this functionality from iOS. Apple’s privacy stance needs to be consistent to believe that they are doing it for the benefit of the user. If they apply strict conditions that limit functionality on the web but allow pervasive tracking in native it can be argued they are providing pervasive tracking in the area which generates revenue while applying heavy restrictions beyond what is needed to prevent tracking on the other side.

5.6. iOS Safari is Buggy

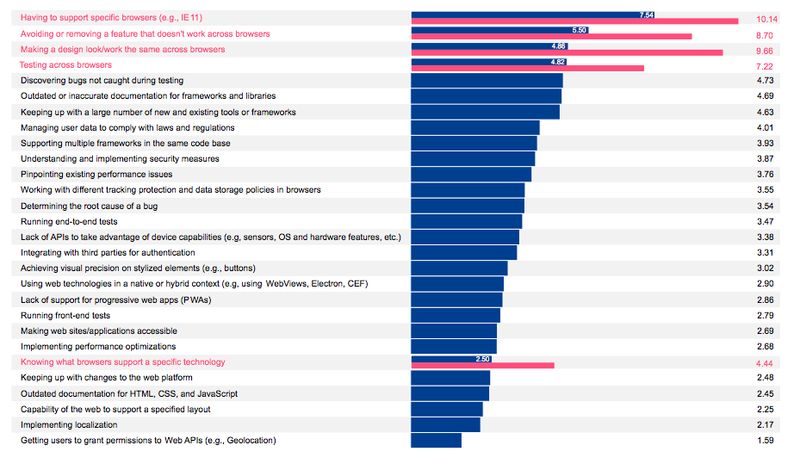

In the Mozilla Developer Network Web Developer Needs Assessment 2020 Survey developers listed browser compatibility issues as the largest issue as defined by:

- Having to support specific browsers (e.g IE 11)

- Avoiding or removing a feature that doesn’t work across browsers

- Making a design look/work the same across browsers

- Testing across browsers

Drilling down further it was specific browsers that were causing the issues.

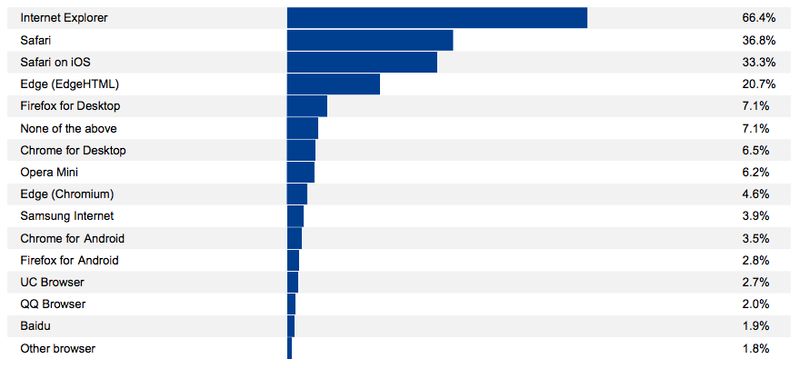

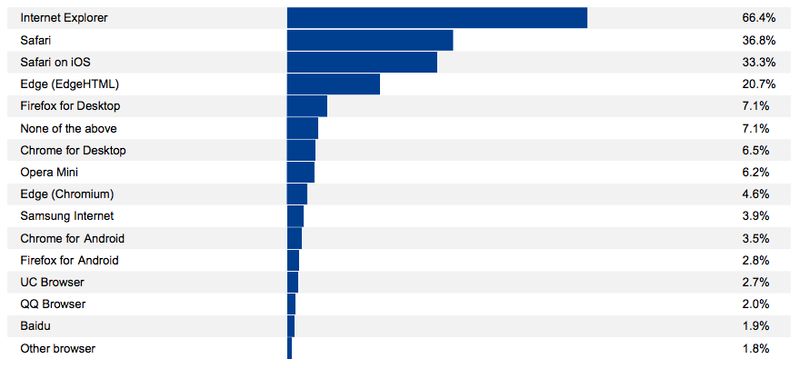

Internet Explorer is at End of Life in June 2022, and has not been in serious development since 2015. This means that Safari causes at least 5 times more issues than the next active browser on the list.

Note that Edge (based on the EdgeHTML engine) has been discontinued and now accounts for much less than 1% of global use. The Edge browser has been rebuilt on Chromium.

This suggests that once Internet Explorer ceases to be used (its usage is already below 1%) than the primary browser causing serious issues for developers will be Safari.

Safari on iOS has had countless, severe application breaking bugs that make it impossible to use as a foundation for a stable application. Furthermore, the mechanism by which updates for Safari on iOS are pushed to users, requiring a full OS update instead of just updating the browser, means it can take multiple weeks, if not months, for a severe bug to be fixed. All this time, Web Apps and sites may be broken or even unusable. This means many companies are forced to develop native applications simply for the stability they provide.

It is important to note that we believe these bugs are likely a result of reverse incentives in relation to the App Store and a lack of competition which has led to a systemic underfunding of the Safari/webkit team for many years. It’s likely that the Safari/Webkit team is working as hard as they can to make a stable browser but just can’t keep up because Apple has not provided enough resources for them to be able to do it.

5.6.1. State of CSS Survey

CSS stands for Cascading Style Sheets which is used for formatting and layout for websites and Web Apps. It is one of the four languages used to develop websites and Web Apps, along with HTML, JavaScript and WebAssembly. It is used in nearly every web page, and is definitionally an uncontroversial core web standard.

The State of CSS survey of web developers recently had a question about "pain points" and "browser incompatibilities". In the raw text of the answers, the yellow lines are the ones that contain the word Safari:

Extracting some of the quotes from the survey, it’s obvious that the opinion among developers that Safari is both buggy and lagging behind features is commonly shared amongst developers. Safari/iOS/webkit/iPhone/ipad was mentioned 369 times several times. By comparison Firefox only had 12 negative mentions in the entire survey.

Here are some extracts from the survey:

I hate Safari with a passion of a thousand burning suns.

Why is Safari so crap? Why on earth do I still have discussions about IE11?

The Safari team should put their head out of their arse - Safari, Especially iOS Safari, are such a pain to work with as a webdeveloper, they lag years behind on too many features for both CSS & JS.

Safari feels pretty behind the times most of the time

Safari is always years behind Edge/Chrome and has many many many bugs related to viewheight/scroll.

iOS Safari is the biggest limiting factor in all web development.

mostly things that safari is catching up on

safari is evil

Flex gap :( it's so good but Safari is the new IE.

Safari is the main problem

Full screen height is a pain to work with in Safari

Still have been held back by IE11, but that ends soon. (Safari though...)

Anything Safari doesn't want to implement

Safari is just weird a lot

Too many to list for Safari on iOS/ipadOS

Only lacking/lagging support in Safari

Safari in general has issues with standards implementation

All of CSS with Safari. Notch specially

All the new stuff being held back by Safari

Anything iOS Safari doesn't support is a blocker, because its rendering engine is mandatory in iOS.

Anything new when using a WebKit browser -.-

Anything related to Apple company, most of the new features are not available over there ;)

Anything safari does not support

Anything Safari doesn't want to implement

Anything that Firefox and Chrome support but Safari doesn't. It's a pain having to account for Apple's low bar.

Anything that’s implemented differently in Safari & iOS Safari

Better Safari update cycle, detached from OS updates

Bugs in Safari related to shadow DOM.

Everything Safari doesn't support but Chromium & Firefox do

Flex gap, damn you Safari!

focus-visible is not yet supported by Safari

For whatever reasons, I wish Safari was quicker at implementing things.

Full screen height is a pain to work with in Safari

height being inconsistent on IOS safari

I hate Safari.

I have more and more instances where stuff works everywhere but not in Safari.

I just treat safari as a hellhole where css goes to die

I often find myself with layout issues that only happen in Safari

I'm not sure exactly what it is, but Safari is now my problem child across all metrics. It seems to be a little different each time, but overall Safari is always the browser with CSS related bugs.

Incompatibilities, poor CSS support in Safari

It is difficult for me to treat Safari as an important testing target or to pretend I care about its compatibility when Apple seems utterly determined to make it difficult to test on Safari, and to use its incompatibilities to hold back open web development on Mac and especially on iOS. I increasingly feel that Safari doesn't really want to be part of a creative or open web, and that's fine I guess, but I'm not going to waste my time and money buying an iPhone to test on when Apple would just prefer I made a native app for their platform anyway.

Just all of Safari.

Just wish Safari would die already

Main CSS pain point above all: Safari (i.e. all iOS) being rigged with bugs and lagging behind in features.

Many technologies blocked by lack of Safari support

Mostly just slow adoption by Safari

mostly things that safari is catching up on

Nearly all pain points are Safari.

Not any specific at the top of my head, but usually Safari is the one giving me a hard time :(

Not many but it's annoying when it happens. It's usually Safari lagging behind or rendering random stuff instead of the UI specified.

Not really difficulties, but Safari is one he** of a pain in the a** and having a more precise way of targeting it instead of both him and Chrome would be great (like -moz- prefix instead of having to write a bunch of @supports)

Only lacking/lagging support in Safari

Perf issues in Safari

Pretty much anything modern, as Safari is lagging behind.

Pretty much anything that Safari shipped less than 18 months ago

REMs in media queries. Damn you Safari!!

Safari (in general)

Safari and apple in general have incompatibility because they are late

Safari became the new Internet Explorer fro us

Safari feels pretty behind the times most of the time

safari has been a bit of a pain

Safari imcompatibilities

Safari iOS is becoming tiresome.

Safari is a huge mess

Safari is always years behind Edge/Chrome and has many many many bugs related to viewheight/scroll. iOS Safari is the biggest limiting factor in all web development.

Safari is constantly dragging its heels.

safari is evil

Safari is just weird a lot

Safari is neglected

safari is pain in the ass for debug if you have pc

Safari is the main problem

Safari is the new IE

Safari is the new Internet Explorer...

Safari on iOS :D

Safari should die!

Safari sucks

Safari updates not frequent enough

Safari, especially mobile

Safari. Everything WebKit. Freaking Apple…

The number one web problem is browser compatibility. Browser like Safari is slowing down the evolution of web unfortunately

Too many to list for Safari on iOS/ipadOS

Using Flexbox to layout forms because Safari on iOS shrinks radio buttons.

we can create any new features, but if browsers (like Safari) are waiting 3 years to implement it, it's totally useless.

WebKit is never up to date and doesn't implement features fast enough (or at all).

yea, loads, mostly because of safari - like gap or ::marker

Yeah Safari is killing me, it's the new IE!

Yep, Safari is the new IE regarding grid and flexbox issues

Yes - and Safari is nearly always the browser that gets it wrong.

Yes, horrible Safari support

Yes, specifically compatibility with Safari

Yes, usually it's Safari. It became new IE😂

Yes. And we have Apple to blame for it! Flexbox gap is a good example.

Yes. Too much new useful features not supported by fcking safari.

5.6.2. WebRTC

WebRTC is a standard for web video calls, access to microphones and cameras, and enables streaming video applications such as game streaming (Stadia, xCloud, Luna, GeForce NOW, etc.).

During March 2020 and the rise of the pandemic in Norway EVERYONE needed video calling. We are the number one video calling tool for healthcare here, and our use base is around 60% iOS Safari. I can tell first hand having to deal with onboarding 70% of the doctors in Norway with active bugs on iOS in simple things like media reliability, and with no real alternative (a lot of people only have one modern device, and that's their phone), it was near catastrophe for us, and a lot of pain for doctors missing their patients due to bugs Das-Igne Aas – CTO Confrere

iOS Safari WebRTC is such a broken mess that my going suggestion to clients unfortunately is to not support it and redirect users to a native app installation. I had to manually go through all open WebRTC bugs in webkit to figure out how to explain this to my clients and help them in reaching that conclusion and even conveying that to their customers.

There are nasty bugs in iOS Safari that have been opened since 2019 or earlier relating to media handling of WebRTC. These aren’t just edge cases, but rather things you’ll have users bump into in regular use. Some of them have finally been fixed in the latest 13.5.5 beta earlier this month.

Oh – and if you plan on using any OTHER browser on iOS then WebRTC won’t be supported there. Why? Because Apple hasn’t made WebRTC available in its Webkit Webview on iOS and they aren’t allowing anyone to build a mobile iOS browser that doesn’t use Webkit as its rendering engine. So much for freedom and choice. Tsahi Levent-Levi

5.6.3. IndexedDB

IndexedDB is a local browser database for storing data. It is essential for many apps, especially apps that require offline functionality. IndexedDB on iOS Safari has had many bugs and been broken many times since it was first introduced. Recently, both IndexedDB and LocalStorage, a similar API for storing small amounts of data, were broken, leaving developers little alternatives to store data or risk data loss or corruption. Local Storage which is also essential for many websites was broken at the same time.

Apple's WebKit team has managed to break the popular IndexedDB JavaScript API in the latest version of Safari (14.1.1) on macOS 11.4 and iOS 14.6. Thomas Claburn - The Register

Ran into a spectacularly awful Safari bug in the latest Safari (14.1.1 on macOS and iOS 14.6).

Opening an IndexedDB database fails 100% of the time on the first try. 😩

If you refresh, it starts working.

Bug report: https://bugs.webkit.org/show_bug.cgi?id=226547It's really really hard to build reliable websites on macOS and iOS with showstopper bugs like this. This should have been caught by basic unit testing. Feross Aboukhadijeh (Stanford Computer Security University Lecturer and Open-Source Developer of Socket)

5.7. Default Browser Choice

Until late 2020, it was impossible for iOS users to choose an alternative browser to handle links, even if they had installed other WebKit-skin browsers from the App Store. Apple continues to prevent competitors from bringing differentiating features via their own engines.

As the only company banning competing engines, Apple is clearly the worst offender, but they are not the only ones impeding user choice. It is our opinion that to preserve competition, users must be given the ability to easily change their default browser and that choice must be respected by the operating system

Google’s “Android Google Search App” has been ignoring browser choice on Android.

Known as the "Android Google Search App" ("AGSA", or "AGA"), this humble text input is the source of a truly shocking amount of web traffic; traffic that all goes to Chrome, no matter the user's choice of browser. Alex Russell - Program Manager on Microsoft Edge

Facebook has been abusing IAB (In App Browsers) to prevent users from opening links from within the Facebook app in either their own browser or in a view that uses the users default browser (both iOS and Android provide this, although the iOS is only iOS Safari).

Using IAB (In App Browsers) to deny users choice is a very complex topic. This article does an excellent summary of the current situation and why it is bad for consumers. We have also made a separate submission covering this topic.

It is our opinion that mass market operating systems and major applications should as much as possible provide users with the means of selecting a default browser (complete with its engine) and respect it. Additionally they should avoid using dark patterns or misleading interfaces to favour their own browser.

5.8. Evidence of Long Term Neglect and Developer Discontent

In addition to 5.6. iOS Safari is Buggy, this section describes some of the long term evidence of neglect and developer discontent with Safari by providing quotes with links to external sources. This evidence is not exhaustive and is simply a subset of what’s available. The sources date from 2011 to 2022.

5.8.1. Push Notifications

Push Notifications for iOS on Native was released on June 17, 2009. As of writing almost 13 years have passed and Apple has provided no mechanism to allow Web Apps to send notifications, a critical feature for many applications.

It is undoubtedly the most requested feature but has been repeatedly ignored by Apple. It was only on September 26th 2021 (after OWA’s #AppleBrowserBan campaign and presentations to regulators) that Apple started work on Push API, although over 200 days later and there have been no indication that this feature will be ready any time soon.

There are countless requests for this feature across platforms frequented by developers including twitter/stackoverflow/reddit and Apple’s own bug tracker.

Developers were so frustrated in the lack of development and response from Apple they started their own change.org petition which has garnered over 7000 signatures, a substantial amount considering how poorly supported Web Apps are on mobile devices.

Extracted from the site are some quotes:

It's hard enough to develop for Apple as is. Stop making it harder for me to make something for your users to use. James Hessell-Bowman (Feb 9, 2022)

(emphasis added)

PWAs are the future. iOS Safari isn't. Change it! Mauricé Ricardo Bärisch (Jan 7, 2022)

(emphasis added)

Safari is the new IE Flavio Spezi (Nov 24, 2021)

My goodness no push notification yet, disgrace Daniel Gadd (Nov 24, 2021)

(emphasis added)

IMHO, PWAs are a better way to reach mobile users, compared to native mobile apps, for not-hardware-intensive apps. Saqib Shafin (Oct 3, 2021)

(emphasis added)

I'm a developer who would like to be able to sell this feature to clients without caveats or additional costs. It would also be great to have a unified web for all platforms. Alex Grant (Jun 26, 2021)

(emphasis added)

Please implement the W3C standards. Don't be like IE or soon the developer community will turn on you. Frank Ali (May 26, 2021)

(emphasis added)

We need this web developers Jack Smith (Apr 29, 2021)

(emphasis added)

Come on guys, we need this... It's crucial. Morne Erasmus (1 year ago)

(emphasis added)

It's the right thing to do Apple. Shaun Bliss (1 year ago)

(emphasis added)

Need it! Soon!! Francesco Rombecchi (Dec 1, 2021)

(emphasis added)

Desperately needed for modern web apps Michoel Samuels (Jun 9, 2021)

(emphasis added)

I would like to write from one codebase and deploy on all platforms David Murdoch (1 year ago)

(emphasis added)

Shocking what they are doing. Pure monopoly. They are lowering the technological progress to protect their pockets, but they are the most rich stock in the world… Federico Schiocchet (1 year ago)

(emphasis added)

This would dramatically simplify some business apps. Ben in CA (1 year ago)

(emphasis added)

It's ridiculous they don't have it! Mohameth Seck (1 year ago)

(emphasis added)

It's sad that we have to petition for something like this. I wonder if Steve was alive if he would hold back the progress of technology like these clowns at apple. Shaquille Hinds (1 year ago)

(emphasis added)